I have always lamented the scarcity of written sources on early medieval cuisine, food that was eaten during the so-called Dark Ages. Surely I don't agree with the idea of 5th-10th European history being the history of Man's decline etc. but when it comes to historical evidence (and its lack), "Dark Ages" sounds like a perfectly good denitinion.

My idea of writing this blog came as I read Jane Austen's Emma but the recipe that's closest to my heart, based on apples, is the 14th century version of apple-tart ('tartys in applis') simply because it's medieval. Unfortunately, original recipes that fall under this category are seldom, if ever, dated before 1300. In fact, Hildegard von Bingen's encyclopaedic notes on food in Physica are just about the oldest medieval recipes we know. Cookbooks that have been saved and made popular owing to Gutenberg's invention are dated from the 13th, 14th, 15th centuries - just before the Early Modern period. So, in truth, nobody really knows what eating was like in the time of Alfred the Great (whether he actually burned those cakes or not), except via indirect sources.

One written source, by a man called Vinidarius, gained popularity during the Carolingian Renaissance, some decades before Alfred's rule. It was claimed to be an extract from Apicius, a compilation of gourmet recipes from the Late Antiquity that was published in the fifth century. Even as such, circulation of Vindicarius' work hoped to preserve the culinary tradition of a world that seemed to be lost and that Charlemagne wished to revive - it certainly did not reflect 8th or 9th century eating habits. Browsing the Forme of Cury, in which the recipe for 'tartys in applis' is featured, and 2-3 other contemporary books also doesn't help understand early medieval cuisine. These books were published 300 years after the Norman conquest of England, a turning point in many aspects of British everyday life, including culinary habits. Similarly, it wouldn't be logical to expect that Alfred or his court (since the king had a nasty complaint, abstaining from rich food) enjoyed those meals from Apicius.

On the other hand, sailing through uncharted waters as historians must do who take an interest in the Dark Ages, allows some kind of freedom - which is not without merit, at least here in this blog. I like to believe that food, as well as other cultural habits of the Saxons, the

Angles, the Welsh, and even the Danes who had already mingled with the

Brits until 1000, was pure, simple & true - like Sir Walter Scott hints in

Ivanhoe - and that nourishing food was available to many in times of good harvest.

|

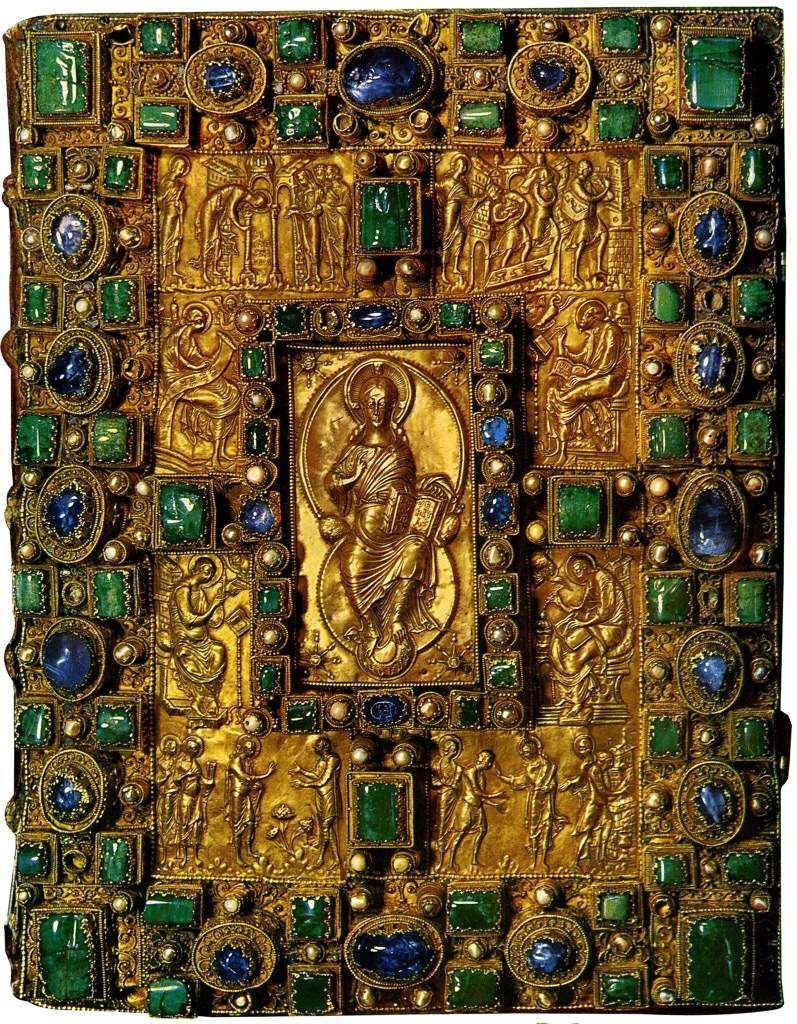

| Jewelled cover of the Condex Aureus of Saint Emmeram (ca. 870) |

A fascinating detail about making guesses at Christmas food before 1000 is that Christian faith was not yet properly established in large parts of the world. Just as interestingly, Christmas food in many European traditions nowadays does not include sweet yeasted bread, which is this blog's guest of honor around this time of the year. Like we've discussed in the posts about Stollen, beigli and Vetekrans, festive versions of yeasted bread that was rich in eggs, butter, sugar and cream, and even stuffed with fruit and nuts, appeared in monasteries where luxury ingredients could be found in abundance. This didn't happen until the end of the Middle Ages or the beginning of the Early Modern period (1600-1800) although noble palates since the Greek and Roman Antiquity already enjoyed baked desserts. Moreover, ancient culinary tradition continued without interruption in the eastern half of the (fallen) Roman empire, aka the Byzantium, where honey cakes of various sizes graced the tables of the rich.

During the Early Medieval period and even later than that, old and new religious customs and habits would mingle, including the food that people ate on special occasions. Meat certainly held a special place in ancient & early medieval feasts and indeed if you google "Christmas food in traditional European cuisines", several dishes of beef and pork will come up, together with rice pudding, which is also featured in late medieval cookbooks - unlike holiday breads. Add that wild yeasts, like sourdough starters, were the main rising agent for centuries, and you will understand why sweet bread rolls were impossible to flourish in the Dark Ages. Even Hildegard's spiced cookies that were supposedly comfort food must have actually been quite heavy and dense.

.JPG)

Comments