Perhaps it rhymes with 'Hansel & Gretel' but it has nothing to do with folklore: this post is dedicated to medieval cuisine.

Simnel became highly popular in England some time during the 17th century. It was a rich plum cake occasionally flavored with saffron and typically made for Lent. Contemporary versions of simnel are filled with a layer of marzipan. The dough is wrapped in paper and slow-baked for about 2 hours so the almond paste doesn't burn. The baked cake is topped with another layer

of marzipan, which is decorated with eleven balls of the same confection representing the 11 Apostles; finally, the surface is egg-washed and grilled for 1-2 minutes. A less complicated yeastbread of the same name was eaten by the nobility during the Middle Ages. It was originally boiled like a pudding and then baked in the oven. No recipe of the medieval version is preserved but its etymology suggests the use of refined wheat flour. (In Latin, simila meant 'finely ground wheat' and siminellus the bread roll made of this flour. The equivalent terms in Middle High German were semele and semmel.)

This kind of simnel bread was probably no more than a white roll. Marzipan and candied fruit were not introduced to Italy, Spain and France by the Arabs until the Late Middle Ages and The Forme of Cury, published in the second half of the 14th century, rarely -if ever- mentions these ingredients. However, it features various recipes for puddings that are colored with saffron and/or enriched with dried fruit. These ingredients might have been added to earlier versions of simnel bread.

An important question is why medieval bakers cooked simnel dough twice. Twice-baked cookies were popular since ancient Rome when early versions of bis-coctum were rationed to soldiers. A hardtack called 'biskit of muslin' would also sustain Richard Lionheart's men on their voyage to Palestine. As for ordinary bread, its production and sale in England was regulated since the reign of Henry II (the father of Richard and John). The rules which applied for the ingredients, shape, weight, quality and price of the bread were officially recorded in the Assize of Bread and Ale (Assisa panis et cervisiae) several decades into the next century. The method of bread preparation was also regulated by this law, affecting the manufacture of baking equipment such as the oven. Although less rich than gingerbread or holiday yeastbreads of the Early Modern period, refined wheat breads during Henry II's time were still complicated to make and simnel was no exception. Another explanation for double-cooking this bread stems from an 18th century pseudo-folk tradition, according to which a couple once quarrelled about the best way to make simnel and decided to first boil and then bake the dough.

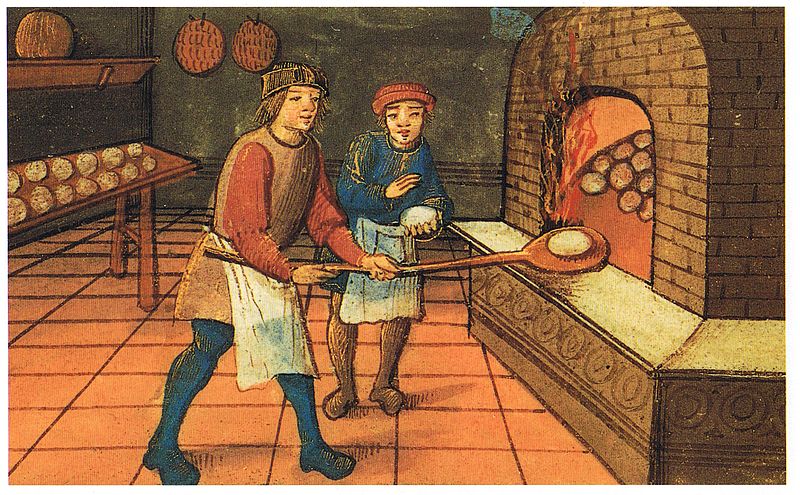

|

| A medieval baker with his apprentice |

The other historic dessert referenced in Ivanhoe is the wastel. Etymologically, this was a soft white bread made of refined wheat flour and possibly leavened with yeast, just like simnel. (The Frankish term wastil is derived from Proto-Germanic wistiz that means 'food' or 'essence'. In Old French, gastel from which gâteau is derived, is based on wastel from the Old English wist that means 'food' or 'essence' and its Latin equivalent wastellus documented in texts from the 1190s.) There was probably no filling here either because The Forme of Cury offers a recipe for 'stuffed wastels': "WASTELS YFARCED. XX.VII. XIX. Take a Wastel and hewe out þe crummes. take ayrenn & shepis talow & þe crummes of þe same Wastell powdour fort & salt with Safroun and Raisouns coraunce. & medle alle þise yfere & do it in þe Wastel. close it & bynde it fast togidre. and seeþ it wel." (This roughly means, "Carve out the crumb of soft white bread. Crumble and mix with eggs, sheep's fat, salt, saffron, and raisins. Fill into the crust, seal the edges and boil.")

Because

'simnel' and 'wastel' had equivalents -if not their roots- in both

Germanic and Romance languages, it's more than certain that similar bread rolls were made in Europe at least since the year 1000. However, Sir Walter Scott distinguished simnel bread and wastel cakes from the 'rich

pastries' offered at Prince John's feast that were likely imported from France, suggesting their Englishness. In the context of Ivanhoe, this meant that Norman and Saxon cultural elements were somehow mingled (in fact, they had merged long before the 1190s) and that local dishes were considered

at least as fine as the others. 'Bad prince' John offered his

guests a sample of both cuisines while, on another pretext, 'good

king' Richard acknowlegded the local drinking habits by wassailing the Saxons. (In Middle English, wassail was an exclamation that meant 'your health'. A hundred years later it also denoted the spiced wine, ale or mead offered to guests of honor, especially around Christmas, and from the 18th century onwards, wassailing is even linked to door-to-door caroling.) In fact, the gap between the local specialties and the Anglo-Norman delights served at Prince John's feast was probably not as big as Ivanhoe suggests. During the 12th century, a

festive meal on the Continent ended with only dragées, mature cheese, and spiced wine; the more sophisticated desserts of which the people who teased Cedric the Saxon (the father of Ivanhoe) would rightly boast of did not yet exist.

In the version shared below, suet is replaced with butter. You might also find it practical to use saffron yeastbread that's already filled with raisins.

|

Comments