Today's guest of honor is the Swedish Tea Ring, a lovely yeastbread usually baked for the holidays. Vetekrans has much in common with the German, Swiss & Austrian (braided) wreath but its history is relatively unknown. Perhaps it's no more than 200 years old because rich cakes, with or without yeast, came into fashion at the beginning of the nineteenth century. But even if the Swedish Tea Ring is often compared to Viennese bread (which is a Danish pastry from the 1850s), its shape reminds of older days.

Naturally, a Tea Ring

made for Christmas would be a symbol of peace, hope and faith. Its

shape would allude to eternal life, or life that goes in circles -which is a

theme we find in most religions. In

ancient or early medieval societies (in which the old was mingled with the new), a wreath has symbolized joy. The bride

and bridegroom were crowned with flowers, leaves, or stems of evergreen

plants fastened on rings. Circular-shaped jewels were also meant to demonstrate power. We

all know stories about magic rings, like the Ring of the Nibelungs or

the One Ring from J.R.R. Tolkien's fantasy novels but the significance of rings has also dominated the customs, habits and beliefs of real people in history. So maybe the idea of an edible wreath (or ring) like Vetekrans originates from pre-Christian times. In Scandinavia, a medieval king or chieftain always wore a finger-ring that indicated his power; similarly, all of his Viking warriors bore arm-rings on which they swore their oath of allegiance. But circular patterns had also other uses.

|

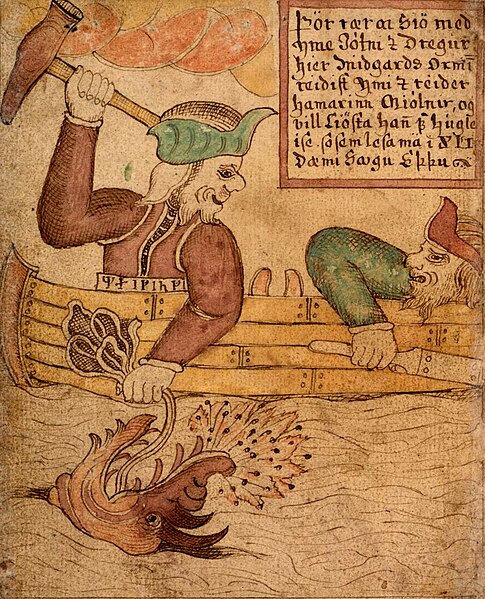

| Thor and Hymir baiting the Midgard Serpent (18th c. Icelandic manuscript) |

Noone would probably think

about the Midgard Serpent while baking a Swedish Tea Ring but here is a

case. According to Old Norse myths and sagas, Jörmungandr -the Huge Monster- encircled the visible world biting its own tail. This notion was not particular to Vikings (who initially believed in the flat earth theory); it rather originated from ancient Egypt, where it symbolized fertility. But the stories preserved in the Eddas are delightful as usual: The Midgard Serpent was born of Loki and the giantess Angrboða, like the Wolf Fenrir and Hel. All three siblings had a part in Ragnarök, the great battle that would destroy Midgard. While Jörmungandr slept, everyone was content but the impending doom worried the gods. Thor confronted the Midgard Serpernt twice before Ragnarök. Prompted by king Útgarða-Loki, he once lifted a cat that was actually Jörmungandr in disguise; another time, he baited the monster with the head of a dead ox while he was fishing on a boat with the giant Hymir. Each of these attempts made Jörmungandr shake the earth while changing position, which frightened men beyond telling. In the last battle, Thor killed the Midgard Serpent and was killed in his turn by Jörmungandr's poison. (I've always been disappointed at this end, which proves that Old Norse gods were mortal.) Scenes from Thor's encounters with Jörmungandr are carved on runestones from the Viking era; they have also been depicted in manuscripts, illustrations and paintings of the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries.

Comments